Divergent Tunnel

Divergentes Tunnel

Tunnel divergente

It is, as the name states, a divergent tunnel, not a pipe. And the section of this tunnel is increasing to the exit

Objectiv:

- reduce the speed of the air in the tunnel

- have higher pressure at the exit

- increase the coupling surface to the external air

Objectiv:

- reduce the speed of the air in the tunnel

- have higher pressure at the exit

- increase the coupling surface to the external air

Es handelt sich dabei um einen Bass Reflex Tunnel (nicht Rohr) dessen Querschnitt progressiv größer wird.

Ziel der Sache:

- Langsamere Luftgeschwindigkeit im Rohr

- Höheres Druck beim Auslass

- Größere Ankopplung zur externen Luft

Ziel der Sache:

- Langsamere Luftgeschwindigkeit im Rohr

- Höheres Druck beim Auslass

- Größere Ankopplung zur externen Luft

Si tratta di un tunnel per il bass reflex. Non di un tubo. La sezione di questo tunnel progressivamente si allarga.

Obiettivo:

- ridurre la velocità dell’aria nel tunnel

- alzare la pressione in uscita

- aumentare la sezione di accoppiamento all’aria esterna

Obiettivo:

- ridurre la velocità dell’aria nel tunnel

- alzare la pressione in uscita

- aumentare la sezione di accoppiamento all’aria esterna

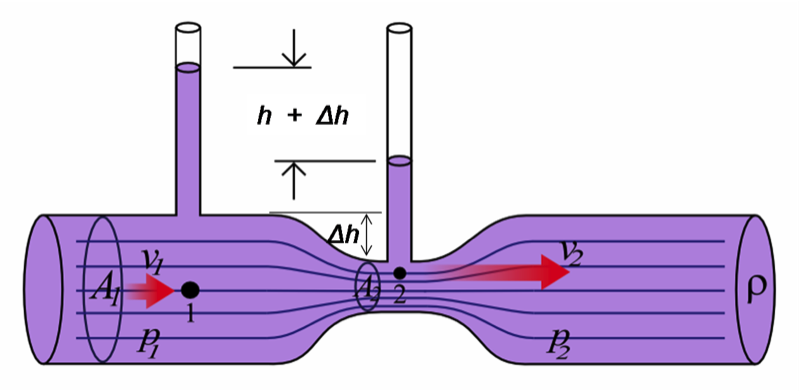

There is a relationship between section, pressure and speed of an incompressible fluid flowing in a divergent or convergent duct. This relationship is known as Venturi-effect: if we consider a volume constant flow, the bigger the section, the smaller the speed and higher the pressure inside the fluid.

The surface at the beginning of the bass reflex or the horn is smaller than the surface at the end of it. This brings a change in the speed and pressure of the flow between entrance and exit. It is a paradox: at the exit is slower and does have more pressure.

Therefore it is clear that this duct is very important for the sound of the loudspeaker.

But. Air is compressible. Therefore the laws and parameters describing the theory of the behavior of the fluid get more and more complex. Just very complex mathematic simulations can show us what the air makes inside the flow. The parameters are, for example, density, viscosity, linear or turbulent behavior of the gas. Then again the form of the exit of the duct influences the turbulence inside the duct and its surfaces define the linearity of the flow or the boundary behavior. The mathematics behind these phenomena are the Euler-equations and the continuity-equation: these are the fundaments behind sound propagation…

If this is not enough, we have to consider that the average volume flow on the exit of a loudspeaker is zero: the loudspeaker does not blow up or out. It is not a constant but an oscillating flow: air is pushed out and then sucked back into the loudspeaker with high strength and high accelerations. Therefore extreme pressure variations occur: as example inside a subwoofer of a dancing floor we have found some tennis balls sucked inside it by the subwoofer itself.

In conclusion, the standard components can not translate the whole experience Blumenhofer Acoustics collected on this matter during the years: therefore it is understandable the high effort in the development of tunnels and horns.

The surface at the beginning of the bass reflex or the horn is smaller than the surface at the end of it. This brings a change in the speed and pressure of the flow between entrance and exit. It is a paradox: at the exit is slower and does have more pressure.

Therefore it is clear that this duct is very important for the sound of the loudspeaker.

But. Air is compressible. Therefore the laws and parameters describing the theory of the behavior of the fluid get more and more complex. Just very complex mathematic simulations can show us what the air makes inside the flow. The parameters are, for example, density, viscosity, linear or turbulent behavior of the gas. Then again the form of the exit of the duct influences the turbulence inside the duct and its surfaces define the linearity of the flow or the boundary behavior. The mathematics behind these phenomena are the Euler-equations and the continuity-equation: these are the fundaments behind sound propagation…

If this is not enough, we have to consider that the average volume flow on the exit of a loudspeaker is zero: the loudspeaker does not blow up or out. It is not a constant but an oscillating flow: air is pushed out and then sucked back into the loudspeaker with high strength and high accelerations. Therefore extreme pressure variations occur: as example inside a subwoofer of a dancing floor we have found some tennis balls sucked inside it by the subwoofer itself.

In conclusion, the standard components can not translate the whole experience Blumenhofer Acoustics collected on this matter during the years: therefore it is understandable the high effort in the development of tunnels and horns.

Es gibt ein Zusammenspiel zwischen Geschwindigkeit, Fläche und Druck eines inkompressiblen Gases der in einem nicht divergentes oder konvergentes Rohr strömt. Dieses Verhältnis wird vom Venturi-effekt beschrieben: bei konstanter Volumenstrom je größer die Fläche desto langsamer die Geschwindigkeit und höher der Druck im Gas.

Die Fläche am Anfang des Bass Reflex Tunnel oder des Hornverlaufes ist deutlich kleiner als die Fläche am Ende. Dies bringt eine Änderung vom Stromgeschwindigkeit und Druck zwischen Einlass und Auslass. Es ist ein Paradox: am Austritt ist langsamer und hat deutlich mehr Druck.

Die Auswahl dieses Verlaufs hat einen erheblichen Einfluss auf dem Klang des Lautsprechers.

Da aber die Luft komprimierbar ist, treten andere physikalische Gesetze und Parameter zum Tragen, die die reine theoretische Berechnung ohne aufwändige mathematische Symulationen unmöglich machen. Die zusätzliche Parameter sind zum Beispiel: Dichte, Viskosität, Lineares oder Turbulentes Verhalten der Luft. Dazu, durch die Form der Abrisskanten kann man mehr oder weniger Turbulenten Strom ins Rohr einfließen lassen und durch die Glätte der Wände im Tunnel kann man die Linearität und den Grenzschicht beeinflussen. Die mathematische und physikalische Beschreibung dieser Phänomene erfolgt durch die Euler-Gleichung und die Kontinuitätsgleichung für ein komprimierbares Fluid: diese sind die Grundregeln die uns erlauben Musik zu hören...

Als Wermutstropfen dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß im Durchschnitt ist der Volumenstrom an der Austrittsfläche gleich null: der Lautsprecher bläst sich weder auf noch ab. Es ist kein konstanter Strom sondern ein schwingender Strom: Luft wird herausgepresst und dann wieder angesaugt und zwar mit viel Kraft und hohe Beschleunigungen. Es bilden sich sehr hohe Druckschwankungen: zum Beispiel haben wir in einem nach Boden gerichteter Subwoofer einer Diskothek sogar Tennisbälle gefunden, die bestimmt nicht hineingeworfenen sondern aufgesaugt wurden.

Ergebnis ist, daß Standardkomponenten können die ganze Erfahrung nicht übersetzen, was Blumenhofer Acoustics zum Thema im Laufe der Jahren gesammelt hat: dementsprechend treiben wir diesen Aufwand für die Entwicklung der Tunnels und Hörner.

Die Fläche am Anfang des Bass Reflex Tunnel oder des Hornverlaufes ist deutlich kleiner als die Fläche am Ende. Dies bringt eine Änderung vom Stromgeschwindigkeit und Druck zwischen Einlass und Auslass. Es ist ein Paradox: am Austritt ist langsamer und hat deutlich mehr Druck.

Die Auswahl dieses Verlaufs hat einen erheblichen Einfluss auf dem Klang des Lautsprechers.

Da aber die Luft komprimierbar ist, treten andere physikalische Gesetze und Parameter zum Tragen, die die reine theoretische Berechnung ohne aufwändige mathematische Symulationen unmöglich machen. Die zusätzliche Parameter sind zum Beispiel: Dichte, Viskosität, Lineares oder Turbulentes Verhalten der Luft. Dazu, durch die Form der Abrisskanten kann man mehr oder weniger Turbulenten Strom ins Rohr einfließen lassen und durch die Glätte der Wände im Tunnel kann man die Linearität und den Grenzschicht beeinflussen. Die mathematische und physikalische Beschreibung dieser Phänomene erfolgt durch die Euler-Gleichung und die Kontinuitätsgleichung für ein komprimierbares Fluid: diese sind die Grundregeln die uns erlauben Musik zu hören...

Als Wermutstropfen dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß im Durchschnitt ist der Volumenstrom an der Austrittsfläche gleich null: der Lautsprecher bläst sich weder auf noch ab. Es ist kein konstanter Strom sondern ein schwingender Strom: Luft wird herausgepresst und dann wieder angesaugt und zwar mit viel Kraft und hohe Beschleunigungen. Es bilden sich sehr hohe Druckschwankungen: zum Beispiel haben wir in einem nach Boden gerichteter Subwoofer einer Diskothek sogar Tennisbälle gefunden, die bestimmt nicht hineingeworfenen sondern aufgesaugt wurden.

Ergebnis ist, daß Standardkomponenten können die ganze Erfahrung nicht übersetzen, was Blumenhofer Acoustics zum Thema im Laufe der Jahren gesammelt hat: dementsprechend treiben wir diesen Aufwand für die Entwicklung der Tunnels und Hörner.

C’è un rapporto tra velocità, sezione e pressione di un gas incompressibile che scorre in un tubo di sezione variabile. Questo rapporto è noto come effetto-Venturi: considerando un flusso a volume costante, quanto più ampia è la superficie, tanto minore è la velocità e tanto maggiore è la pressione all’interno del fluido.

La superficie all’inizio del tunnel del bass reflex o della tromba è decisamente minore della superficie alla sua fine. Questo porta una variazione della velocità flusso e della pressione del fluido tra ingresso ed uscita. È un paradosso: all’uscita è più lento ed ha più pressione.

Quindi è chiaro che la definizione di questo canale ha un notevole influsso sul suono.

Però l’aria è comprimibile. Quindi sono altre le leggi ed i parametri che permettono un calcolo teorico e la descrizione del fluido nel dotto è solo possibile con simulazioni matematiche estremamente complesse. Un esempio dei parametri: densità, viscosità, comportamento lineare o turbolento del gas. In più la forma del tubo in uscita permette di influenzare la turbolenza nel tunnel. Le pareti più o meno lisce influenzano la linearità e lo strato limite. La descrizione matematica e fisica di questi fenomeni è presa dalle equazioni di Eulero e dall’equazione di continuità per un fluido comprimibile: questi sono i fondamenti che ci permettono di ascoltare musica…

Se poi non bastasse, dobbiamo ricordarci che in media il flusso volumetrico in uscita da un diffusore è zero: il diffusore non si gonfia ne si sgonfia. Non è un flusso costante ma un flusso oscillante (spero che sia la definizione giusta): l’aria viene spinta fuori e poi di nuovo riaspirata e con molta forza ed altissime accelerazioni. Quindi si formano estreme variazioni di pressione: per esempio, il subwoofer di una discoteca non suonava più, era rivolto verso il pavimento ed al suo interno abbiamo trovato anche delle palle da tennis che di sicuro nessuno aveva infilato dentro ma erano state aspirate.

Per concludere, le componenti standard non possono tradurre tutta l’esperienza che Blumenhofer Acoustics ha raccolto su questo tema nel corso degli anni: quindi è comprensibile il grandissimo impegno che profondiamo nello sviluppo dei tunnel e delle trombe.

La superficie all’inizio del tunnel del bass reflex o della tromba è decisamente minore della superficie alla sua fine. Questo porta una variazione della velocità flusso e della pressione del fluido tra ingresso ed uscita. È un paradosso: all’uscita è più lento ed ha più pressione.

Quindi è chiaro che la definizione di questo canale ha un notevole influsso sul suono.

Però l’aria è comprimibile. Quindi sono altre le leggi ed i parametri che permettono un calcolo teorico e la descrizione del fluido nel dotto è solo possibile con simulazioni matematiche estremamente complesse. Un esempio dei parametri: densità, viscosità, comportamento lineare o turbolento del gas. In più la forma del tubo in uscita permette di influenzare la turbolenza nel tunnel. Le pareti più o meno lisce influenzano la linearità e lo strato limite. La descrizione matematica e fisica di questi fenomeni è presa dalle equazioni di Eulero e dall’equazione di continuità per un fluido comprimibile: questi sono i fondamenti che ci permettono di ascoltare musica…

Se poi non bastasse, dobbiamo ricordarci che in media il flusso volumetrico in uscita da un diffusore è zero: il diffusore non si gonfia ne si sgonfia. Non è un flusso costante ma un flusso oscillante (spero che sia la definizione giusta): l’aria viene spinta fuori e poi di nuovo riaspirata e con molta forza ed altissime accelerazioni. Quindi si formano estreme variazioni di pressione: per esempio, il subwoofer di una discoteca non suonava più, era rivolto verso il pavimento ed al suo interno abbiamo trovato anche delle palle da tennis che di sicuro nessuno aveva infilato dentro ma erano state aspirate.

Per concludere, le componenti standard non possono tradurre tutta l’esperienza che Blumenhofer Acoustics ha raccolto su questo tema nel corso degli anni: quindi è comprensibile il grandissimo impegno che profondiamo nello sviluppo dei tunnel e delle trombe.

Venturi-Effect, Wikipedia